THE WORKS OF HUBERT HOWE BANCROFT - VOLUME XIX

HISTORY OF CALIFORNIA

Vol. II. 1801-1824

SAN FRANCISCO

1885

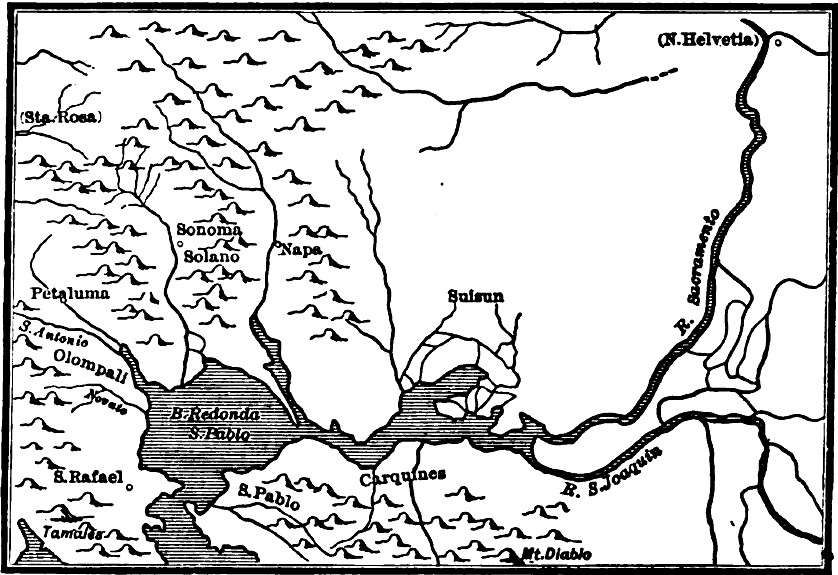

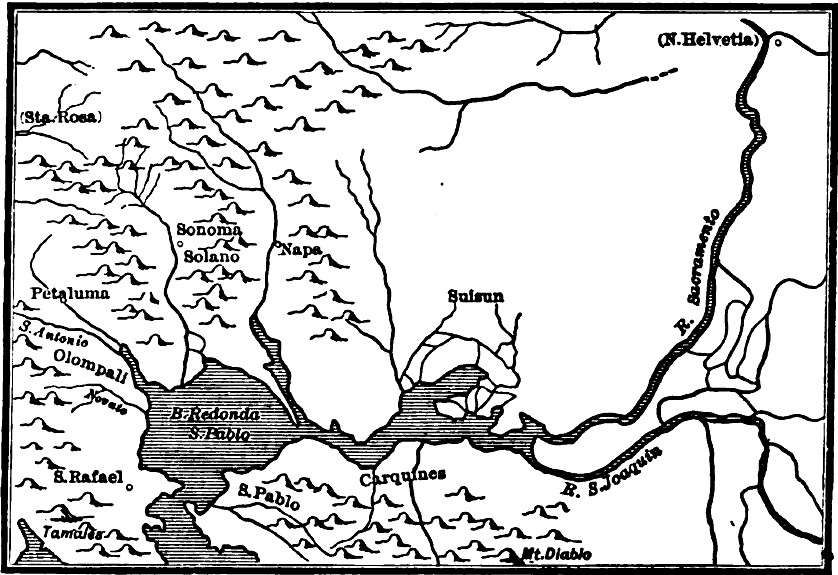

MORAGA'S 1810 FIGHT AT SUISUN

Page 91

The Indians were somewhat more troublesome in 1810 than they had been before, both in the north and south; and Alferéz Moraga, preeminently the Indian-fighter of the time, was kept very busy in the Spanish acceptation of the term. In May he was sent with seventeen men to punish the gentiles of the Sespesuya rancheria who lived across the bay from San Francisco, apparently near the strait of Carquines in the region of Suisun, and who for several years had committed depredations, killing sixteen neophytes from San Francisco. The Spaniards crossed the strait in a boat and after a hard fight with one hundred and twenty pagans, captured eighteen of the number, who were released as they were almost sure to die of their wounds. The survivors retired to their huts and made a brave resistance, wounding two corporals and two soldiers. The occupants of two of the three huts were defeated and all killed; but when the other hut was set on fire with a view to drive out the occupants they bravely preferred to perish in the flames. Arrillaga having sent an account of this brilliant affair to Mexico, and the viceroy having transmitted it to Spain, there came back a royal order expressing the satisfaction of the council of regency, in the king's name, at the glorious action of May 22, 1810. By the terms of this order Moraga was promoted to a brevet lieutenancy. Corporals Herrera and Francisco Soto, wounded, were made sergeants; the wounded soldiers, Antonio Briones and Ventura Zuniga, were given a slight increase of pay, while the others who shared in the action were rewarded with the thanks of the nation.24

24 June 28, 1810, Arrillaga's report to viceroy. Prov. Rec, MS., ix. 122-3. Nov. 12, 1811, viceroy to gov., enclosing royal order of Aug. 19th. Prov. St. Pap., MS., xix. 314. June 26, 1812, governor to Com. Estudillo, transmitting viceroy's communication. Prov. Rec. MS., xi. 222-3. Vallejo, Hist. Cal., MS., i. 131-5, in describing a fight in the same region by José Sanchez in 1817 against the Suisunes under chief Malaca, states that the Indians set fire to thie huts and temescales in which they had taken refuge, and perished in the flames. It is possible that the author has confounded two different battles. Alvarado, Hist. Cal., MS., i. 69-70, makes the date 1817, but puts Gabriel Moraga in command, and says that Samyetoy, afterward known as Solano, was captured on this occasion.

References:

History of California (1876) by Mariano Vallejo (Mexican General)

Historia de California (1876) by Juan Bautista Alvarado (Governor of California)

Manuscripts for both of the above sources are in the collection of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley

SANCHEZ & ABELLA's 1811 EXPEDITION TO SUISUN

Pages 321-323

The annals of inland survey for the decade open with an exploration of the lower San Joaquin by water. This visit to a region so near the settlements and already more or less well known to the Spaniards might be deemed hardly worth notice as an exploration; yet by reason of its local importance, its minuteness, and its application of early and original names, I have thought the diary worthy of reproduction in substance in a note.1 Padre Abella was accompanied by Padre Fortuni of Mission San José; Sergeant Sanchez seems to have commanded the expedition. The force is said to have been composed of sixty-eight persons, saihng in several boats. After giving to points San Pablo and San Pedro in the bay the names which they still bear, the party went up the western and down the eastern channels of the San Joaquin, which name, however, they did not use, though it had been applied earlier to the same river, choosing to re-name it, or particularly the eastern or main branch, Rio de San Juan Capistrano. Crossing over into the Sacramento through the Two Mile Slough, they descended that river to its mouth—its first definitely recorded navigation—calling it Rio de San Francisco, a name they understood to have been previously applied. Thence after a visit to the country of the Suisunes, they returned home after an absence of fifteen days. Friendly intercourse was held with the Indians, who were very numerous on the Sacramento, and a few of the aged and sick were baptized. The Suisunes showed more timidity than hostility. The shores of the Sacramento offered a favorable site for a new establishment, though somewhat difficult of access.

1 Abella, Diario de un registro de los rios grandes, 1811, MS. The same expedition is briefly noticed by Mofras, Exploration, i. 450, who adds: 'Le journal

manuscrit de cette exploration interressante est entre nos mains.'

Oct. l5th from the presidio anchorage to Angel Island in A.M. and in P.M. as soon as the tide was favorable, to Pt Huchones (name of the Indians there). Between Angel Island and points Huchones and Abastos is formed a bay twice as large as that at the port, with 8 islands, mostly small, one of which has to be passed on the way to Huchones. This island has a bar visible only at low

water, and most be passed on the west at a little distance.

Oct. 16th gave to Pt Huchones the name Pt San Pablo and to the opposite point (probably the one before called Abastos) that of San Pedro (both names still retained). These points, with two little islands between, close the first bay and begin another much larger one (San Pablo Bay). There are 5 gentile rancherias on the north and west. On the west enters an estero, said by the Indians to be large (Petaluma Creek), but Moraga has been round it twice—A league and a half to another point named San Andres (Pt Pinole). The intermediate country is all 'mainland of San José,' belonging to the Huchones, mostly bare but with a few oaks and a fine stream (where San Pablo now stands)—To the Strait of the Karquines ending the bay and formed between the 'tierra firme de San Josef' and at first an island (Mare Island) but farther on mainland also on the north—Through the strait to its end in the country of the Chupunes, where there are mud flats and a dangerous concealed rock. Place called La Division.

Oct. 17th, into a large bay (Suisun Bay) where the water gradually becamefresh—About 18 leagues eastward (clearly erroneous as are nearly all the distances of the diary) along the southern shore, past islands, tules, and swamps, into a right-hand channel, to camp on an island (Brown or Kimball Island) which was a fishing station of the Ompines.

Oct. 18th, back half a league to take the left-hand channel, though there was no need as the branches came together again—Eastward past another island, (Kimball's or West's) past a widening whence a passage (Three Mile Slough at head of Sherman Island, explored on the return) led through into the northern River of San Francisco (Sacramento)—Half a league farther on turned into the right-hand and smaller branch (The West Channel of the San Joaquin), and sailed southward in a winding course with nothing in sight but water and tule and sky, sleeping on the boats for want of a landing.

Oct. 19th-22d, still up stream through the tules southward and eastward to the Pescadero rancheria on an island (the name had been given before and is still sometimes applied on modern maps to the southern end of Union Island) belonging to the Cholbones—Thence eastward (noting the middle channel and southern slough of modern maps) into the main river, which they named the San Juan Capistrano (San Joaquin). At or near the junction they set up a cross, and supposed themselves on the parallel of San José, (though really opposite San Francisco). At the junction of the southern slough farther up (just above the present railroad bridge. It is not clear that this party went up there) was the rancheria of the Cosmistas—Thence down the main stream (East Channel) to the rancheria of the Coyboses.

Oct. 23d-27th, down the river to the branch followed up from the 18th (mouth of West Channel)—through the passage before noticed (at head of Sherman Island) northward into the San Francisco (Sacramento), naming the numerous Indians apparently Tarquimenes—and down the river to the junction, saying mass at the Loma de los Tompines, opposite the Cerro' Alto de los Bolbones (which was perhaps Mt Diablo). The country on the San Francisco (Sacramento) is described as well fitted for settlement, but accessible only by water, by crossing either at the presidio or at the Strait of Karquines—Thence northwardly through an estero (Montezuma Creek and Nurse Slough) to a spot one league from the plain of the Suisunes.

Oct. 28th-30th, one league to the head of Suisun Creek, and the edge of the largo fine plain dotted with oaks. The Cerro de los Bolbones was about 12 leagues s.w. (s.e.?) Two rancherias were Suisun and Malaka, and another at a little distance was Ulululo. Two leagues distant was where Moraga's famous battle took place. On the 29th the voyagers returned to Angel Island; and spent all the next day in getting across to the presidio against unfavorable wind and tide.

SANCHEZ 1817 FIGHT AT SUISUN

Pages 328-329 (under notes)

Vallejo, Hist. Cal., MS., i. 144-6, mentions, as having occurred in 1816, an expedition under Arguello and Padre Ordaz to the far north, in which the chief Marin was captured in Petaluma valley; but the reference must be to a much later expedition—in fact Ordaz did not come to the country until 1820. The same writer, Id., i. 151-5, and also Alvarado, Hist. Cal., MS., i. 69-70, evidently confound another expedition, which they put in 1817, with Moraga's famous battle of 1810 (see chap, v, of this vol.) Vallejo puts Sanchez in command of the Spaniards, Malaca of the Suisunes, and says the latter set fire to their own huts and perished in the flames. Alvarado puts Moraga in command, and says that Sam Tetoy, afterwards known as Solano, was captured. It is not unlikely that these writers confound Moraga's expedition of 1810 with some other actually made in 1817. Vallejo's account of the campaign is found also in California Jour. Senate, 1850, p. 531-2; and in Solano Co. Hist., 9, 17-18.

References:

Journal of the Senate of the State of California, Report by M.G. Vallejo, April 16, 1850.

ABELLA'S 1817 JOURNEYS

Pages 329-330

14 Jan. 20, 1817, Sola writes to the viceroy that since his arrival he has ordered 7 expeditions against the pagans, all resulting favorably. Prov. Rec., MS., ix. 168. Jan. 22d, Duran proposes to explore in May the place where the fugitives are, so as to prepare a plan for their capture. His weapons will be a santo cristo and a breviary, but he would also like a canoncito for the secular branch of the expedition. Ten men and a pedrero were promised. Arch. Arzob., MS., iii. pt. i. 124-5. June 1st, Abella reports a visit to the gentiles who generally ran away from their rancherias. He proposes a military visit to where a neophyte and his wife are urging resistance and arguing that 'tambien los soldados tienen sangre.' Id., iii. pt. i. 136-7.

[It seems likely that Sergeant José Sanchez accompanied Abella on his 1817 "visit to the gentiles" and/or conducted the subsequent military visit proposed by Abella. One or both of these visits probably coincides with the 1817 fight with the Suisunes that Mariano Vallejo writes about, and most likely confuses with Moraga's more famous and better documented 1810 battle.]

It was in 1817 that the Spaniards founded their first establishment north of San Francisco Bay. The mortality among the Indians at San Francisco had become alarming and was likely to create a panic, when Sola suggested as a remedy for the evil the transfer of a part of the neophytes across the bay. Some were sent over as an experiment, greatly to the benefit of their health; but at first the president, while approving Sola's plan, hesitated about the formal transfer for want of friars, and because of the difficulties of communication.- At last when several neophytes had died on the other side without religious rites Padre Luis Gil y Taboada, late of Purisima, consented to become a supernumerary of San Francisco and to take charge of the branch establishment.15

15 Sarria, Informe del Prefecto, Nov. 1817, MS., p. 73-6. The determination was to found 'a kind of rancho with its chapel, baptistry, and cemetery, with the title of San Rafael Arcangel, in order that this most glorious prince, who in his name expresses the 'healing of God," may care' for bodies as well as souls. Sola gives the same reasons for the new foundation in his letter of April 3, 1818, to the viceroy. Prov. Rec., MS., ix. 777. Dec. 10, 1817, Sarria writes to Sola that on Saturday next he will go over with Duran. Arch. Arzob., MS., iii. pt. ii. 21.

[text omitted]

The site was probably selected on the advice of Moraga, who had several times passed it on his way to and from Bodega;A though there may have been a special examination by the friars not recorded. Father Gil was accompanied by Duran, Abella, and Sarria, the latter of whom on December 14th, with the same ceremonies that usually attended the dedication of a regular mission, founded the asistencia of San Rafael Arcangel, on the spot called by the natives Nanaguani. Though the establishment was at first only a branch of San Francisco, an asistencia and not a mision, with a chapel instead of a church, under a supernumerary friar of San Francisco; yet there was no real difference between its management and that of the other missions.

A [Bancroft reports on v. 2, p. 324 that Gabriel Moraga in 1812-14 made three trips to Bodega and Ross.]

SANCHEZ and ALTIMIRA'S 1823 EXPEDITION TO SUISUN

Pages 497-499

An exploration was next in order, for the country between the Suisunes and Petalumas was as yet very little known, some parts of it never having been visited by the Spaniards. With this object in view, Altimira and the diputado, Francisco Castro, with an escort of nineteen men under alferéz José Sanchez, embarked at San Francisco the 25th of June, and spent the night at San Rafael. Both Sanchez and Altimira kept a diary of the trip in very nearly the same words, the substance of which I reproduce in a note so far as names, courses, and distances are concerned, omitting necessarily much descriptive matter respecting a country since so well known.33 The explorers went by way of Olompali to the Petaluma, Sonoma, Napa, and Suisun valleys in succession, making a somewhat close examination of each. Sonoma was found to be best adapted for mission purposes by reason of its climate, location, abundance of wood and stone, including limestone as

was thought, and above all for its innumerable and most excellent springs and streams. The plain of the Petalumas, broad and fertile, lacked water; that of the Suisunes was liable more or less to the same

objection, and was also deemed too far from the old San Francisco; but Sonoma as a mission site, with eventually branch establishments, or at least cattle-ranchos at Petaluma and Napa, seemed to the three

representatives of civil, military, and Franciscan power to offer every advantage. Accordingly on July 4th a cross was blessed and set up on the site of a former gentile rancheria, now formally named New San Francisco. A volley of musketry was fired, sacred songs were sung, and holy mass was said. July 4th might, therefore, with greater propriety than any other date be celebrated as the anniversary of the foundation, though the place was for a little time abandoned, and on the sixth all were back at Old San Francisco.

CONTRA COSTA OF THE NORTH-EAST

33 Sanchez, Diario de la Expedition verificada con objeto de reconocer terrenos para la nueva planta de la Mision de San Francisco, 1823, MS. The departure of Sanchez and the number of his men are stated in St. Pap. Sac., MS., xi. 16.

Altimira, Diario de la Expedition, etc., MS. This diary was also translated by Alex. S. Taylor, and published in Hutching's Mag., v. 58-62, 115-18, as the Journal of a mision-founding exjiedition north of San Francisco in 1823. Though there are many verbal differences between the two diaries, it is evident that they were not written independently from day to day. Probably

Sanchez used the friar's MS. in making out his narrative. Taylor's translation is often inaccurate.

The diary is in substance as follows:

June 26th, in the morning from S. Rafael, 5 leagues north to Olompali; in afternoon, north and round the head of the creek at the point called Chocuay (where the city of Petaluma now

stands, the main stream being apparently called Chocoiomi) to the little brook of Lema on the flat of the Petalumas, where a bear was killed, and where they passed the night with 8 or 10 Petalumas hiding there from their enemies of Libantiloyami, or Libantiloquemi (the Libantiliyami of chap. xx.), 3½ l. to the N.W. (I think this Arroyito de Lema may have been some distance down the creek.)

June 27th, over the plains and hills, eastward and north-eastward, past a small tule-lake 50x100 yards, and a little farther the large lake of Tolay, so named for the chief of the former inhabitants, one fourth of a league long by 150 or 200 yds. to ¼ league wide (perhaps they were as far south as the lake back of the modern Lakeville), and thence N.E. to the plain on which is the

place called Sonoma, so called from the Indians formerly living there, camping on the stream near the main creek, where a boat arrived the same day from S. Francisco. (Sonoma had probably been visited before.) Payeras in 1817 used the name of Sonoma as well as Petaluma. chap. xv. The arrival of the boat and also the mention of the name coming from former inhabitants point in the same direction though there is no definite record of any previous visit. This afternoon and the next forenoon they spent in exploring the valley.

June 28th, in the afternoon they crossed over the hills north-eastward to the plain, or valley, of Napa (so accented in the original of Altimira), named for the former Indian inhabitants, and encamped on the stream (Napa Creek) which they named San Pedro for the day. A whitish earth on the borders of a warm sprmg thought to be valuable for cleansing purposes, and large herds of deer and antelope were noted on the way.

June 29th, crossed over another range of hills into the plain 'of the Suisun,' so called like the other places from the former Indian inhabitants (generally called in earlier documents 'of the Suisunes' as the name of the Indians), camping on the main stream 5 l. from Napa, 101. from Sonoma, and 5 l. S.W. of the rancheria of the Hulatos. June 30th, killed 10 bears, and had some

friendly intercourse with the Lybaitos. (In a letter of July 10th, Arch. Arzob., MS., iv., pt. ii. 23-6, Altimira gives more particulars of his conference with the Indians, by which it appears that the Lybaitos lived about 3 l. beyond [N.E.] the Hulatos, or Ulatos. The rancherias of the Chemocoytos, Sucuntos, and Ompines are mentioned in the same region.)

July 1st, back to Napa and Sonoma with additional explorations of the latter valley. July 2d, up the valley and over the hills by a more northern route than before, past a tule lake, into the plain of the Petalumas, and to the old camping-ground on the Arroyo de Lema. July 3d, back by a direct course of 2 leagues to Sonoma, where after new explorations a site was chosen. July 4th, ceremonies of taking possession, and return to Olompali, 6 long leagues. July 5th, back to San Rafael and waited for the boat from Sonoma. July 6th, embarked at Point Tiburon and went to San Francisco before the wind.

THE WORKS OF HUBERT HOWE BANCROFT - VOLUME XX

HISTORY OF CALIFORNIA

Vol. III. 1825-1840

SAN FRANCISCO

1886

MENTIONS OF FRANCISCO SOLANO (CHIEF SOLANO)

Pages 294-295

We know only that at the ex-mission of San Francisco Solano, where he had spent much of the time for nearly a year as comisionado of secularization, Vallejo established himself with a small force in the summer of 1835, and laid out a pueblo to which was given the original name of the locality, Sonoma, Valley of the Moon, a name that for ten years and more had been familiar to the Californians. Vallejo soon gained, by the aid of his military force, and especially, by alliance with Solano, the Suisun chief, a control over the more distant tribes which had never been equalled by the missionary and his escolta, a functionary who, however, still remained as curate. Quite a number of families, both Californians and members of the famous colony, settled at Sonoma.

Page 360

In 1835 Vallejo seems to have marched northward from Sonoma to aid the chief, Solano, in reducing the rebellious Yolos.25 He had in view also an expedition to the Tulares in July; but it was given up.

25 Vallejo, Report on County Names, 1850, p. 532, in Cal., Journal of Senate, 1850. Charles Brown claims to have accompanied an expedition apparently identical with this. He says the force consisted of 60 Californians, 22 foreigners, and 200 Indians, lasting nearly three weeks in the rainy season. 100 captives were taken, and some acts of fiendish barbarity were committed by Solano and his men. Narrator was wounded.

Page 456

Next Don Juan Bautista hastened to Sonoma, receiving aid and encouragement along the way from the rancheros and others at San José, San Francisco, San Pablo, and San Rafael, at which latter place the padre invited him to take the benefit of church asylum. At Sonoma he found his uncle Vallejo more cautious and less enthusiastic in the cause than he would have wished. The comandante

was very strong and independent, monarch of all he surveyed on the northern frontier, and correspondingly timid about running unnecessary risks. While patriotically approving the views of Alvarado and his

associates, and ready in theory to shed his blood in defence of popular rights, he counselled deliberation, remembered that the northern Indians were in a threatening attitude, required time to put his men in a proper condition to leave their families, and after a ceremonious introduction to the chief Solano and his Indian braves at Napa, sent his nephew in a boat to San José with instructions to rouse the people and await further developments.

Page 598

About this time the chief, Solano, conceived the project of making a visit to Monterey with an escort of Indian braves. He had been invited by Alvarado in 1836 to pay him a visit, and had promised to do so; but his action at this time was doubtless prompted by Vallejo, who thought it well to frighten the potentates of the capital with a hint at his reserve power. He of course had no real intention of inflicting on the people of Monterey a large force of Indians; but he perhaps at first exaggerated the number to be sent.38 In the middle of October, the general announced that

Solano had asked and received permission to visit the capital with eighty Indians. I do not know if the visit was made; but if so, it was probably with a smaller number, who formed part of the general's escort, as he was at San Francisco October 22d and 23d, en route to Monterey." 39

38 Sept. 3d, Pablo de la Guerra, in the name of his own and other Sta Barbara families, protests against V.'s proposed sending of Solano with 2,000 Indians. He begs V. not to run such a risk for the sake of frightening Alvarado. Vallejo, Doc., M.S., viii. 73. Oct. 2d, Salv. Vallejo to Guerra. Has urged his brother in vain not to send Solano to Monterey. Hopes to influence Solano, however, not to take more than 1,000 Indians. Id., viii. 192.These letters purport to be copies of originals, and are in the handwriting of a man whom I have often detected in questionable practices. Doubtless the numbers are pure inventions, and the dates are suspicions. Possibly the whole is a forgery, but it is not unlikely that Vallejo may have made a threat and used large figures.

39 Oct. I6th, V. to Alvarado, announcing Solano's departure. Vallejo, Doc., MS., viii. 210. Ochenta in the original is changed clumsily into ochocientns

by the same genius mentioned in the last note. Document also in Dept. St. Pop., MS., iv. 282. Proofs of V.'s trip and presence at S. Francisco on Oct. 22d-3d, and indications that he had 31 men in all. Vallejo, Doc., MS., Yiii. 219, 223, 225. Dorotea Valdes, Reminis., MS., 7-8, claims to remember Solano's visit at Monterey. Fernandez, Cosas de Cal., MS., 96, 101-3, remembers his

passing through S. José with hundreds (!) of Indians. He says Solano kept his men in very good order, but both he and V. acted in a very proud, arrogant manner.

Page 670

3 Summary and index of events at Monterey: [title to a note that does not appear until page 670.]

1839. Feb.-March, public reception to Alvarado; sessions of the assembly. Vallejo, Doc. MS, xxxvi, 584 et seq. May, elections for congress and junta. Id., 589-90. July, arrival of J. A. Sutter on the Clementina, iv. 127. Aug., visit of the French man-of-war Artemise, Laplace com. Id., 154-5. Marriage of the gov., and festivities at the capital. This vol., p. 593. Oct., visit of the chief Solano and his Indians from Sonoma. Id., 598-9.

Pages 722-723

20 Summary and index of events at Sonoma: [title to notes that do not appear until pages 722-723.]

1837. Gen. Vallejo's efforts to enlist and drill recruits; Capt. Salvador Vallejo made mil. comandante, the general going to Monterey Jan.-March. This vol., 511-12. June, campaign of Salv. Vallejo and Solano against the Yolos; capture of Zampay; treaty with Sotoyomes. Vol. iv., p. 72.

Vallejo had many difficulties to contend with, but his zeal and energy in this cause were without parallel in California annals; and the credit due him is not impaired by the fact that the development of his own wealth was a leading incentive. His Indian policy was admirable, and in the native chief Solano he found an efficient aid. For the most part at his own expense he supported the regular presidial company, organized another of native warriors, kept the hostile tribes in check by war and diplomacy, protected the town and ranchos, and, in spite of the country's unfortunate political complications and lack of prosperity, established a feeling of security that in 1839 had drawn 25 families of settlers to the northern frontier.

1839. Oct., Solano's visit to Monterey. This vol., p. 589.

1840. Salv. Vallejo commandant; cavalry and infantry companies as before. In April there was a serious rising of the native infantry, who attacked the cavalry, and being repulsed joined the hostile chiefs of savage tribes. They were in turn attacked by Pina and Solano with a force of soldiers and friendly Ind., and were defeated with much loss. Subsequently two savage chiefs and 9 other Ind. were shot. Vallejo believed the rebels had an understanding with the Sacramento tribes. Vol. iv., p. 12, 74. Aug. 20th, order of Mex. govt to constitute the northern frontier into a comandancia militar. Vallejo, Doc., MS., x. 223.

MENTIONS OF FRANCISCO SOLANO (CHIEF SOLANO) cont.

Vol. IV. 1841-1845

Pages 70-3

Turning now to the northern frontier, we find a different state of things. Here there was no semblance of Apache raids, no sacking of ranchos, no loss of civilized life, and little collusion between gentile and Christian natives. The northern Indians were more numerous than in the San Diego region, and many of the tribes were brave, warlike, and often hostile; but there was a comparatively strong force at Sonoma to keep them in check, and General Vallejo's Indian policy must be regarded as excellent and effective when compared with any other policy ever followed in California. True, his wealth, his untrammelled power, and other circumstances contributed much to his success; and he could by no means have done as well if placed in command at San Diego; yet he must be accredited besides with having managed wisely. Closely allied with Solano, the Suisun chieftain, having always —except when asked to render some distasteful military service to his political associates in the south—at

his disposal a goodly number of soldiers and citizens, he made treaties with the gentile tribes, insisted on their being liberally and justly treated when at peace, and punished them severely for any manifestation of hostility. Doubtless the Indians were wronged often enough in individual cases by Vallejo's subordinates; some of whom, and notably his brother Salvador, were with difficulty controlled; but such reports have been greatly exaggerated, and acts of glaring injustice were comparatively rare.

The Cainameros, or the Indians of Cainamá in the region toward Santa Rosa, had been for some years friendly; but for their services in returning stolen horses they got into trouble with the Satiyomis, or Sotoyomes, generally known as Guapos, or 'braves,' who in the spring of 1836, in a sudden attack, killed twenty-two of their number and wounded fifty. Vallejo, on appeal of the chiefs, promised to avenge their wrongs, and started April 1st with fifty soldiers and one hundred Indians besides the Cainamero force. A battle was fought the 4th of April, and the Guapos, who had taken a strong position in the hills of the Geyser region, were routed and driven back to their rancherías, where most of them were killed. The expedition was back at Sonoma on the 7th, without having lost a man killed or wounded.'

On June 7th Vallejo concluded a treaty of peace and alliance with the chiefs of seven tribes—the Indians of Yoloytoy, Guilitoy, Ansactoy, Liguaytoy, Aclutoy, Churuptoy, and the Guapos—who had voluntarily come to Sonoma for that purpose. The treaty provided that there should be friendship between the tribes and the garrison, that the Cainameros and Guapos should live at peace and respect each other's territory, that the Indians should give up all fugitive Christians at the request of the comandante, and that they should not burn the fields. It does not appear that Vallejo in return promised anything more definite than friendship. Twenty days later the compact was approved by Governor Chico. A year later, in June 1837, Zampay, one of the chieftains of the Yoloytoy —town and ranchería of the Yoloy, perhaps meaning of the 'tules,' and which gave the name to Yolo county—became troublesome, committing many outrages, and trying to arouse the Sotoyomes again. The head chief of the tribe, however, named Moti, offered to aid in his capture, which was effected by the combined forces of Solano and Salvador Vallejo. Zampay and some of his companions were held at first as captives at Sonoma; but after some years the chief, who had been the terror of the whole country, became a peaceful citizen and industrious farmer.55

In January 1838 Tobias, chief of the Guilucos, and one of his men were brought to Sonoma and tried for the murder of two Indian fishermen. In March some of the gentile allied tribes attacked the Moquelumnes, recovered a few stolen horses, and brought them to Sonoma, where a grand feast was held for a week to celebrate their good deeds. In August, 50 Indian horse-thieves crossed the Sacramento and appeared at Soscol with a band of tame horses, their aim being to stampede the horses at Sonoma. Thirty four were killed in a battle with Vallejo's men, and the rest surrendered, the chief of the robbers named Cumuchí being shot at Sonoma for his crimes. On October 6th Vallejo issued a printed circular, in which he announced that Solano had grossly abused his power and the trust placed in him, and broken sacred compacts made with the Indian tribes, by consenting to the siezure and sale of children. Vallejo indignantly denied the rumor that these outrages had been committed with his consent; declaring that Solano had been arrested, and that a force had been sent out to restore all the children to their parents.59

55 June 25th–26th, M. G. Vallejo to Salvador and Jesus, his brothers. Vallejo, Doc., MS., iv. 250, 256. July 26th, Alvarado thanks Salvador for his gallant achievement. Id., xxxii. 104. Salvador Vallejo, Notas, Hist., MS., 7–95, gives many details of the campaign. Vallejo, Hist. Cal., MS., iii. 230–8, 268–9, tells us that just before this expedition he organized a company of 44 Suisunes and Napas, armed and equipped like Mexican soldiers, which was £ under the command of Lieut Sabas Fernandez and given to Solano as a body-guard, much to his delight. This writer also relates, Id., p. 299-304, that Succara, chief of the Sotoyomes, frightened at Zampay's defeat, came to Sonoma and made a treaty, which in 11 articles is given. This may be a confused memory of the earlier treaty already noticed. A treaty of Dec. 1, 1837, with some eastern tribes, is also referred to in a letter of April 1, 1838. Vallejo, Doc., MS., v. 65.

59 Oct. 6th, Vallejo's circular. Earliest Print.; Vallejo, Doc., MS., v. 194; xxxii. 156; S. Diego, Arch., MS., 208; Dept. St. Pap., Ang., MS., x. 23. In his Hist. Cal., MS., iii. 329–38, Vallejo explains that 'certain persons' desiring to injure him brought sundry barrels of liquor to Soscol, made Solano and other chiefs drunk, and thus induced them to consent to the capture of the children, about 30 of whom were sold south of the bay. All were recovered, and Solano, after being sobered for a time in the calaboose, was very penitent. Mention also in Alvarado, Hist. Cal., MS., iv. 216–17; Carrillo, Narrative, MS., 1–3; Fernandez, Cosas de Cal., MS., 96.

Page 444-45

The only document of the year [1844] that throws light on the names of these newcomers is a defence which Benjamin Kelsey found it necessary to make of his character and conduct in

September. Dr Bale, for firing a pistol at Salvador Vallejo, by whom he had been flogged, had been seized by Solano and his Indians at Sonoma, where Colonel Vallejo, having rescued him from the Indians before they could hang him, had locked him up to await trial.

Page 674

Ranchos of northern Cal., granted in 1841–5. [title to a note that does not appear until page 674.]

Suisun (Solano), 4 l., 1842, Francisco Solano; Arch. Ritchie cl.; also J. H. Fine.

|